Nature | News Feature

How China is rewriting the book on human origins

Fossil finds in China are challenging ideas about the evolution of modern humans and our closest relatives.

Jane Qiu1 July 2016

On the outskirts of Beijing, a small limestone mountain named Dragon Bone Hill rises above the surrounding sprawl. It was here, in 1929, that researchers discovered a nearly complete ancient skull that they determined was roughly half a million years old. Dubbed Peking Man, it was among the earliest human remains ever uncovered, and it helped to convince many researchers that humanity first evolved in Asia.

Since then, the central importance of Peking Man has faded. Although modern dating methods put the fossil even earlier — at up to 780,000 years old — the specimen has been eclipsed by discoveries in Africa that have yielded much older remains of ancient human relatives. Such finds have cemented Africa’s status as the cradle of humanity — the place from which modern humans and their predecessors spread around the globe — and relegated Asia to a kind of evolutionary cul-de-sac.

The Neanderthal in the family

But the tale of Peking Man has haunted generations of Chinese researchers, who have struggled to understand its relationship to modern humans. “It’s a story without an ending,” says Wu Xinzhi, a palaeontologist at the Chinese Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (IVPP) in Beijing. They wonder whether the descendants of Peking Man and fellow members of the species Homo erectus died out or evolved into a more modern species, and whether they contributed to the gene pool of China today.

Keen to get to the bottom of its people’s ancestry, China has in the past decade stepped up its efforts to uncover evidence of early humans across the country. It is reanalyzing old fossil finds and pouring tens of millions of dollars a year into excavations. And the government is setting up a US$1.1-million laboratory at the IVPP to extract and sequence ancient DNA.

Finds in China and other parts of Asia have made it clear that a dazzling variety of Homo species once roamed the continent. And they are challenging conventional ideas about the evolutionary history of humanity.

(Polite neurotypical social-speak) “Many Western scientists tend to see Asian fossils and artefacts through the prism of what was happening in Africa and Europe,” says Wu. “But it’s increasingly clear that many Asian materials cannot fit into the traditional narrative of human evolution.”

Human migrations: Eastern odyssey

Aye, yai, yai! Neurotypical nuttiness in a nutshell!

Obviously, there are MANY possible routes given the vast expanse that ‘humanlike animals” have traveled and occupied and the time-frames involved. These diagrams are very simplistic and rely heavily on the “notion” that H. erectus, et al, had “destinations” that match our concept of intent, planning and “destiny or fate” – leading to Homo sapiens.

Evolving story

In its typical form, the story of Homo sapiens starts in Africa. The exact details vary from one telling to another (an understatement), but the key characters and events generally remain the same. And the title is always ‘Out of Africa’.

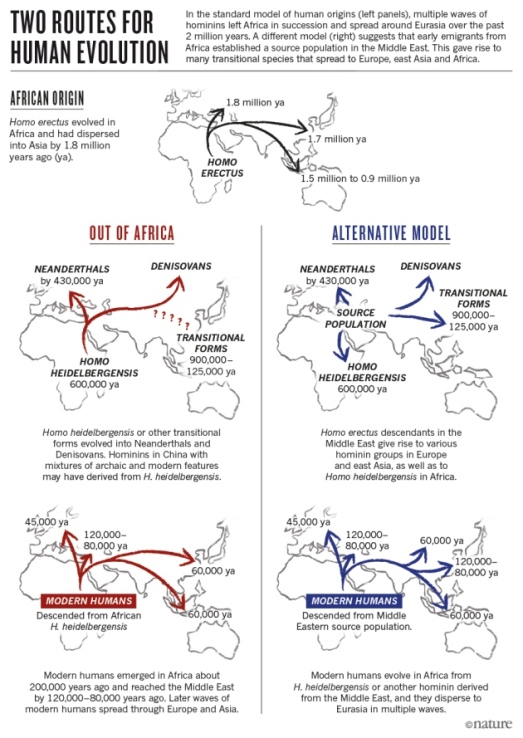

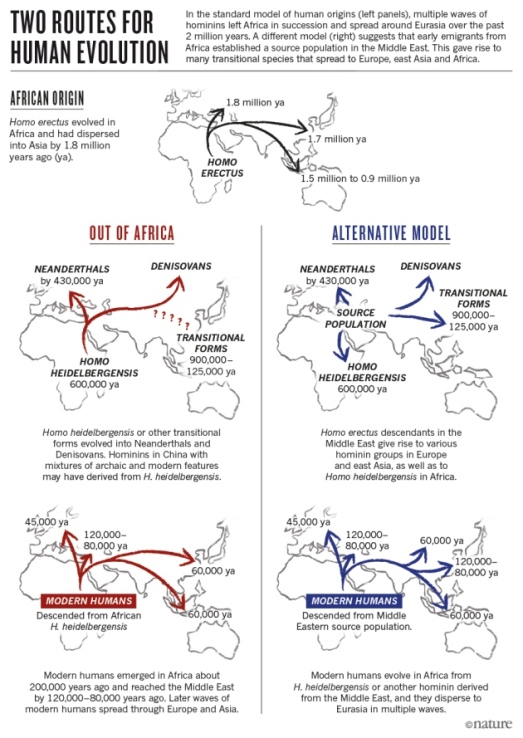

In this standard (western) view of human evolution, H. erectus first evolved (in Africa) more than 2 million years ago (see ‘Two routes for human evolution’). Then, some time before 600,000 years ago, it gave rise to a new species: Homo heidelbergensis, the oldest remains of which have been found in Ethiopia. About 400,000 years ago, some members of H. heidelbergensis left Africa and split into two branches: one ventured into the Middle East and Europe, where it evolved into Neanderthals; the other went east, where members became Denisovans — a group first discovered in Siberia in 2010. The remaining population of H. heidelbergensis in Africa eventually evolved into our own species, H. sapiens, about 200,000 years ago. (Is H. heidelbergensis a distinct species from H. erectus, or late H.e.? And what happened to H. heidelbergensis in the Middle East and Europe from 400k.y.a. – 60,000k.y.a.?) Then these early humans (African H. sapiens) expanded their range to Eurasia 60,000 years ago, where they replaced local hominins with a minuscule amount of interbreeding. (What is a “miniscule” amount of interbreeding? Two actual living beings of possibly different species, or closely related species, must have sex to interbreed; how many “couples” engaged in this is an odd question. Got drunk at the prom, and shagged a Neanderthal? OOPS! Sorry for that alien bit of “nDNA” in your genome.)

For a relatively straightforward presentation of this particular paleoanthropological monstrosity, go to: http://australianmuseum.net.au/homo-heidelbergensis

I have to stop here and rant: this is where my Asperger brain goes absolutely BERSERK:

I feel like I’m watching an episode of “Hoarders” – in which some unfortunate person’s brain is simply “stuck” – and unable to evaluate the difference between the actual function of an object, “it’s reality” and the supernatural-emotional-belief system that imparts fantastic meaning and importance to an empty Kleenex box.

The total obsession with the “structure” relied upon to evaluate human evolutionary history, that is, the archaic “museum drawer” catalog of “What species is it?” and it’s fixation on a linear timeline from past to present, is absurd, when no one is capable of defining “species” as it applies to the human animal and it’s history. Nor is this “structure” questioned as a “match” to the new evidence that continues to be accumulated.

And – making it all worse – The projection of neurotypical narcissists that “ancient people” were just as socially screwed up as they are!

This stubborn obsession demonstrates the “neurotypical” profound lack of imagination.

Imagination? Pink elephants, unicorns, psychedelic color schemes? No: REALITY – specifically, how Nature works, requires a negation of human prejudice, a loss of affection for supernatural explanations, and a rejection of inelegant forms of understanding: if your only “tool” is Legos, everything you construct will be Lego – reality. If your only tool is “What species is it?” you end up with a garage full of cardboard boxes (labeled species x, or species y) stuffed with plastic bags, old clothing, broken tools and moldy food – and whatever else you have dragged home. “Cleaning house” does not mean moving a pile of old magazines and worn out shoes from one box to another.

Lego species.

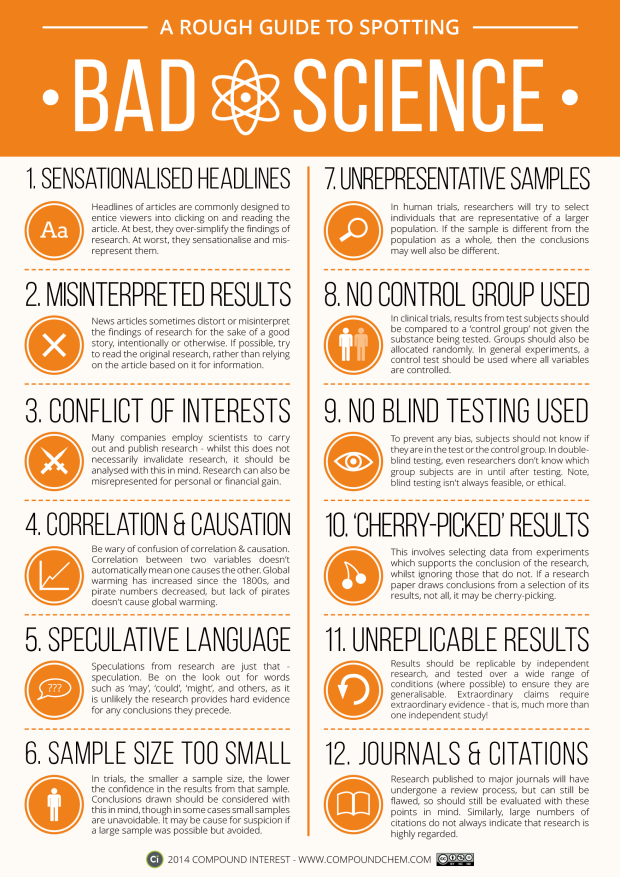

Anthropologists are arguing over which yarn “belongs” in each cubby, when the fossil, DNA, genetic and geologic-geographical as well as spatio-temporal evidence look nothing like this.

What’s the point? The inability to let go of no-longer useful explanations requires setting aside the mental structures that inhibit radical, imaginative thinking, which the history of scientific breakthroughs clearly demonstrates as necessary to the process of “imagining reality”.

Remainder of “China” article: Jane Qiu1

Robin L. Cautin

Robin L. Cautin